How deep is your love?

How deep is your love?

That’s an interesting question for those who study occupational interests. How well-anchored is this preference for helping people, creating stuff and solving puzzles in your personality? Is the interest for quilting, playing the trumpet, making others laugh, building, sports or wild animals real? The love of your life? Or is it just a fling, a whim, a typical case of puppy love?

Some interests come and go and some interests stay with you and are an integral part of who you are and what you do. How do we know what’s what? In this article, we introduce a simple model that will help strengthen your grip on the elusive phenomenon of interests. We start by introducing two dimensions, Intensity and Anchoring.

Intensity

In this model, the Intensity-dimension is linked to the emotional elements of the psychological makeup of an individual.

Low intensity interest refers to a mild emotional response to the subject and high intensity interest refers to intense, passionate feelings.

A high ‘score’ on the Intensity dimension is like falling in love, including the chemical, physiological and behavioural effects. The individual likes it very much, feels really good when it’s there, can’t get enough of it and misses it badly when it isn’t there.

Anchoring

To get an idea about the other dimension, let’s go maritime. Firstly, think of depth. As in deep water versus shallow water. It’s easy to imagine a ‘shallow preference’ for someting: there is a certain level of interest, but it just doesn’t go that far. And along the same lines, it’s imaginable to think of an interest that would go ‘deeper’.

This analogy is a step in the right direction, but ‘depth’ is not quite the right label. ‘Anchoring’ is. In our thinking, a preference can be well-anchored in someone’s personality and behaviour. Or it can be ‘un-anchored’, in other words: not bound, loosely or not-at-all tied to personality or behavioural patterns. It is free to come and go as its pleases. For this ‘un-anchored’ state, we use the label fleeting.

Knowledge

In contrast to the Intensity dimension, where there is an emotional element at play, the Anchoring dimension contains an intellectual element. Having a well-anchored interest implies you ‘know your stuff’: you have knowledge about the subject, you probably like to extend your knowledge and insight, you probably know why this particular subject is interesting to you and you have knowledge about alternatives and variants of the subject.

With a fleeting interest, you’re probably not that knowledgeable. Not that motivated to gather more information about the subject. There is not a lot of commitment to the subject. You tend to accept and be satisfied with your current level of insight.

The fleeting aspect also suggests that one subject could be easily replaced by another. The interest is not ‘anchored in your system’, so ‘letting it go’ and focusing on something else does not take a lot of effort. Consciously or subconsciously cutting the old subject loose is easy. There was never a strong bond to begin with.

Four quadrants

Now we have established two dimensions, it is possible to have a look at some combinations and interactions to see what we can learn from this.

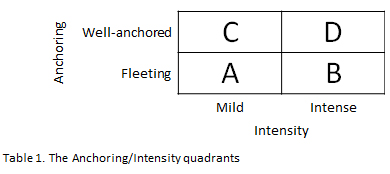

We imagine a perfect world, in which Anchoring and Intensity are comparable and mutually exclusive, so we can place Intensity on the X-axis and Anchoring on the Y-axis. On the X-axis, a low position is called Mild and a high position is called Intense. On the Y-axis, a low position is called Fleeting and a high position is called Well-anchored. This creates four quadrants. Each quadrant should contain typical characteristics and/or typical behaviour, see Table 1.

In a layout like this, usually A and D are the easy to understand quadrants, with clear-cut positions. B and C are more complicated and therefor more interesting and instructional. Let’s see how this turns out.

Quadrant A. Mild and Fleeting interests.

The interests in this quadrant can be viewed as a whim. There is not a lot of intensity or passion, not a lot of eagerness to do or learn more. Perhaps the individual was introduced to the subject by coincidence, perhaps it was peer pressure or another form of social influence. The individual can be seen as a consuming, passive ‘follower of fashion’.

An example of Quadrant A interest is the world wide surge in applications for forensic sciences studies as a result of the popular CSI- series.

Quadrant B. Intense and Fleeting interests.

The interests in this quadrant can ignite quickly and burn out quickly. The individual can be passionate and involved for some time and lose interest abruptly.

So what causes the change from being active and eager to getting detached and losing interest? Obviously, the personality of the individual plays an important part. Some people just have a strong need for change. But the main factor for reaching the tipping point has to do with the downsides of the activity. An example is getting injured in sports: it’s no more fun if you can’t participate on the level you’re used to.

An important indicator for Fleeting interests is a lack of (prior) knowledge. Not knowing exactly what you’re getting in to. Underestimating drawbacks, ignoring warnings, underestimating the required effort. Individuals with a Fleeting interest tend to overestimate their long term motivation. It’s fun as long as it’s easy. But the love diminishes fast when they are confronted with setbacks. Real life quadrant B- examples are:

- Some time after his promotion, the team leader discovers that ‘being a leader’ actually means ‘solving problems you didn’t cause, while still having to do your old job’. A few months ago, he wanted the team leader position so badly he could almost taste it. Now he’s not so sure anymore.

- Simone loves the status connected to being a management trainee in a world leading company, but she hates the competitive ‘up or out’-culture. She would like to be important, but without having to deal with the stress.

- A teenage sporter reaches his limits. Instead of putting in more effort, he blames the equipment and expects mom and dad to pay for better stuff. “Otherwise, I might as well give up".

Quadrant C. Mild and Well-anchored interests.

In this quadrant, there is an unmistakeable need to do certain things, but it doesn’t have to be grand, compelling or dramatic.

‘Mild and Well-anchored’ could refer to activities or opportunities that seem not very important when they are present, but become a real issue when they are lacking. A real life- example is Joline, an introverted back-office sales assistant. She never visits clients, she doesn’t travel for work and that’s fine by her. Except for the yearly trade fair. For exactly three days each year, Joline gets to work outside the office and meet with clients. That’s less than 1% of her working year. At the trade fair, she doesn’t have an important role. She smiles and shakes hands. But still she wouldn’t miss it for the world and she would be very angry if she wasn’t allowed to participate.

Quadrant C interests can pop up from time to time and they are a perfect fit for projects. Lots of workers will welcome a challenging project: it’s an extra effort, but it’s also a break from the usual routines. It could be ad hoc organizing the introductory course for new colleagues, it could be a recurring activity, like doing the admin for your friend’s web shop or it could be volunteer work during your summer holiday.

While these examples appear to be obvious actions to inject a little bit more variation in one’s life or career, the importance of Quadrant C interests must not be underestimated. For a career counsellor this is the quadrant where a little bit of finetuning can have a big impact. It can change the clients outlook on life. To illustrate this point, we’d like you to meet Paul the engineer.

Paul, 51, is an engineer in a chemical plant. A few years ago, he had no energy, no intellectual challenges in his work and no opportunities to change to another job at his level. His expertise had moved him into a golden cage. Financially, he couldn’t take the risk to move to another company.

Paul got depressed by the idea of staying in the same situation for another 15 years or so. He was close to a burn-out, the production manager directed him to have a chat with the HR department. They introduced him to Lola. After completing the questionnaire, he started thinking about teaching as an extra activity. When he was a student, he had contemplated that option, but it hadn’t crossed his mind since. The questionnaire rekindled his ideas about how nice it would be to transfer his knowledge to motivated and talented young engineers. The outcomes of Lola confirmed this: strong preferences for helping, coaching and teaching and a real need to be challenged intellectually.

Thanks to a bit of gentle pressure applied by the HR department, he now is a part time teacher at a technical university. Absolutely nothing has changed about his day job, but he enjoys it more than ever. And that's because he has found a way to address an neglected interest. It's only few hours each week, but it made a big difference.

Quadrant D. Intense and Well-anchored interests.

The interests in this quadrant are serious and persistent.

The individual likes something, wants to do more of it, wants to get better at it and knows a lot about it. The individual is well aware of the challenges and downsides and still is eager to engage in the preferred activity. Actually, this happens quite often: think about having a hobby you can hardly afford or a interesting, but badly paid job.

Quadrant D interests tend to be interwoven with other aspects in the life of an individual. A hobby can start simply as just an activity you like to do. After a while, it can become a way of life, the base of your social network, the place where all your friends are. Also, quadrant D interests can ‘run in the family’. Everybody knows examples of families with lots of teachers / pigeon fanciers / stamp collectors / musicians / athletes / hunters and so on and so on.

Intense and Well-anchored interests are easily recognisable, because there will be behavioural evidence. Important to remember for career counsellors as well as their clients: these strong, fixed interests are hard to ignore and hard to change.

To conclude

The case of Paul the engineer illustrates the power of finetuning. Having detailed knowledge about the interest profiles of your clients pays off, because it saves time and prevents your client from wasting energy. Thinking in terms of Anchoring and Intensity will help you in getting a better understanding of what is needed to make your client happy at his or her work.

Making clients happy is probably one of your Quadrant D activities. So by using the knowlegde you just acquired, you will be happy because you've made your client happy. How cool is that?