Changing interests

(How) do vocational interests develop over time? A conceptual analysis.

Introduction

In this article, we want to share some of our insights into the matter of adult vocational interest development. These ideas were recently published as a book chapter in a new book on vocational interests in the workplace edited by Prof. Christopher Nye (Michigan State University) and Prof. James Rounds (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign), two leading academics in the field of vocational interests. Endorsed by the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology board, this book is a valuable resource for researchers, professionals, and educators in the field of human resources, organizational behavior, and industrial or organizational psychology.

Bart Wille and Filip De Fruyt, both Ghent University, were invited to contribute to this book with a chapter on adult interest development. This was a great opportunity to develop and share some new ideas on how vocational interests might change over time, after people have entered the labor market. We are excited to share some of these ideas with you through this article.

“I loved my job when I started it ten years ago, but for a while now I simply don’t get enough satisfaction out of it anymore”

Why is this topic relevant for Lola-users?

There is an important group of Lola-users who are about half-way (or even further) in their careers and start having doubts about the continuation of their professional activities. These are people who feel or suspect that their interests have gradually shifted over time and they use Lola to check this assumption and get an update on their interest profiles.

You can also think about this issue from a corporate HRM perspective. When you hire young adults, say 25-year olds with little to no experience on the labor market, it is unrealistic to expect that these young wolves have their professional interests perfectly crystallized. To some extent, they have yet to experience certain work activities and, from there, refine (or even reappraise) their preferences. As an HR professional, you want to have your finger firmly on the pulse of any developments in that area. If people are no longer happy with what they are doing, there is a bigger chance that they will lose their motivation and, eventually, leave.

Until now, however, little is known about adult interest development. We have all seen examples of it, but what are the underlying mechanisms and how should we understand this phenomenon? What exactly makes interests change over time? And what are the consequences?

In our contribution to Vocational Interests in the Workplace, we aimed to provide some answers to these fundamental questions.

A summary of the ideas

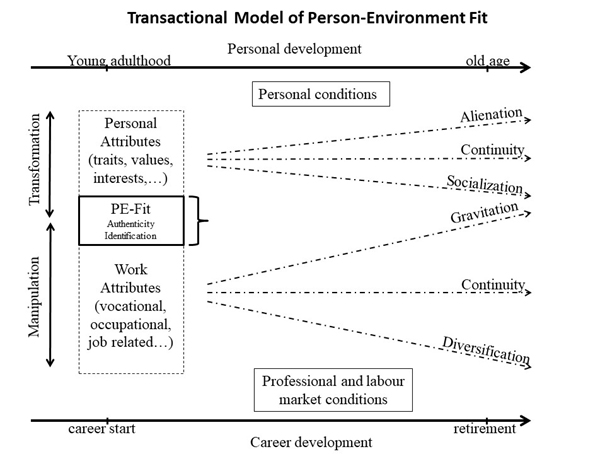

After thinking about these questions thoroughly and based on the scarce empirical research available on this topic, we developed a new theoretical framework to structure our ideas. We used the well-known principle of Person-Environment Fit to guide the theory development. The resulting model is displayed below.

Yes, we are fully aware that there are a lot of boxes and arrows in this scheme. Let us walk you through some of the main ideas and illustrate you how the model works.

Personal development and career development go hand in hand

The basic logic behind the model is that people’s personal development and their career development do not happen in isolation, but instead interact with each other over time. This is the ‘transaction’-part of the model.

How you develop as a person (your personality traits, vocational interests, values etc.) has an influence on how you develop professionally (choice of your career, your effectiveness and satisfaction at work etc.) and vice versa! This also means that professional development can only be fully understood when people’s personal development is taken into account. Multiple life domains overlap and interact.

This overlap in particular between the characteristics of you as a person and the characteristics of your professional environment is captured in this model by an intersection. In the model, this is represented by the box with the curly bracket. It is in this intersection that people can feel authentic at work (‘what you do aligns with who you are’) and helps you to identity with work (‘my work is a part of how I define myself’). This intersection is what we mean by person-environment fit and it plays a crucial role in our theory on adult interest development.

P-E fit is a sweet spot

Based on decades of research on the conditions that make people happy and successful across different life domains, we concluded that Person-Environment (P-E) fit must be one of the driving forces behind interest development. Modern theory on life-span development explicitly states that attaining a satisfying level of fit or ‘congruence’ between one’s personal attributes and one’s environment is a fundamental life task and an indicator of developmental success.

This is just a complex way of saying: it really helps you when you can do stuff that you enjoy doing and that you are good at. In short; P-E fit acts as an incentive, both for the individual and the environment. For the individual, fit is a source of satisfaction and fulfillment. For the environment, fit means that people are more productive.

P-E fit is dynamic

It should not come as a surprise when the model further states that fit is not something that you are born with. And if you can ever reach it (which we REALLY hope you do!), there is no guarantee that you will have it for the rest of your life. In other words, fit can be seen as a dynamic construct which develops over time.

Indeed, as shown in the model, this intersection between personal attributes and work attributes can become larger (fit increases) or smaller (fit decreases) as time goes by. Given that fit is represented as the intersection between personal and work-related attributes, fit changes can result from changes situated at both sides of the equation.

When fit changes as a result of changes in work-related attributes, we call this manipulation.

When fit changes as a result of changes in person-characteristics, we call this transformation.

Below, we zoom in on how these manipulation and transformation effects can take place and give a couple of concrete examples.

A series of fit dynamics

Manipulation

Let’s focus on manipulation first. Work can change either towards or away from one’s personal attributes. This leads to the following two manipulation effects in the model:

Gravitation

Gravitation reflects changes in work in the direction of person-characteristics. In other words, work changes and becomes more aligned with one’s defining traits. The intersection widens and the level of P-E fit thus increases. The typical example is someone switching to a new job which is more closely aligned with one’s interests. This might be something Lola-users are looking for. An alternative example might be ‘changed work content’ in the same job: You ask your boss to do more tasks in line with what you are good at or like.

We also speculated on what this could mean for the direction and nature of interest development. One hypothesis is that gravitation could lead to interest specialization, where people narrow down their interest profile and specifically deepen those preference fields that align with what they currently are doing. Most of us know such a narrow-minded specialist that fits this description, right?

Diversification

Diversification is the term used to describe changes in work away from one’s personal attributes. Schematically, this means that the intersection between person- and work-characteristics shrinks and P-E fit decreases. Most of us know someone who ended up in a job that really did not speak to the person’s interests. Maybe it’s even you who is in this situation!?

One relevant question in this context is: what happens then to one’s interest levels? For instance, can one learn to ‘grow’ an interest in work activities that one initially did not like at all? To what extent? Under which conditions? We can speculate. But honestly, at this point there’s simply not enough empirical data to draw any firm conclusions.

Transformation

Changes can also take place with respect to the person. Depending on the direction of this change, the model distinguishes between two types of transformation effects: Socalization and Alienation.

Socialization

Socialization happens when people’s features become more aligned with their professional environments. The idea is that people gradually adjust to the demands and characteristics of an environment and, as a result, become more similar. Schematically, this means that the intersection between P and E characteristics widens and thus fit increases.

Alienation

Alienation is the opposite process where person-characteristics have changed such that they became less aligned with one’s professional environment. We all know someone who gradually (or suddenly) lost interest in the type of work (s)he was doing. If this sounds familiar, it might be advisable to try and find out how far exactly you have alienated from your current job and what to look for in a job that may prove to be a better fit.

To conclude

This is basically how the model works. It is a theoretical exercise, so it is normal that it all sounds a bit abstract to you. Also, because it is a model, it's normal that you have the feeling that it simplifies a number of phenomena that are in reality far more complex. But that is what theoretical models are supposed to do. At best, it may provide you with some initial insights into the processes going on when looking at people and how they develop over time while crafting a career.

Want to know even more? Send us an email to receive a preprint of this book chapter.

Wille, B. & De Fruyt, F. (2019). The development of vocational interests. In C. D. Nye & J. Rounds (Eds.), Vocational Interests in the Workplace: Rethinking Behavior at Work. SIOP Organizational Frontiers Series.